Virtual Tour

Tour of our Buildings

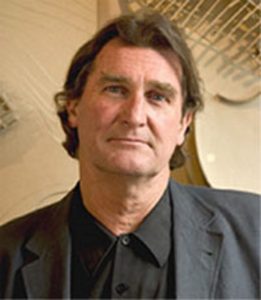

The East Melbourne site of Catholic Theological College brings together the historic bluestone of the original Parade College, designed by William Wardell, and the award-winning architecture of Gregory Burgess, whose creative designs earned him the Royal Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal in 2004.

The site was the winner of the Heritage Property Award (2001) of the Australia Property Institute, and the subject of commendation in the 2000 Victorian Architecture Awards of the RAIA in 2000.

1999 Knox Lecture “The Spirit in Architecture”

In 1999, Gregory Burgess delivered the annual Knox Lecture at CTC, reflecting on the building design.

“The Spirit in Architecture” By Gregory Burgess

I live my life in growing circles

which layer themselves over the world

perhaps I will not complete the last

though I will try.

I circle around God, around the ancient tower,

I circle a thousand years long

And I do not know still

Am I a hawk, a storm

Or a great hymn

Like Rilke the great German poet in his love poems to God, our striving to understand who we are through our lives and work is a mysterious and elusive journey. It has an inner sense with an outer expression which is sometimes in harmony, at times contradictory. A continual metamorphosis of being and becoming.

Architecture has the potential to nurture and extend our sense of who we are as individuals, community or nation by helping us find our relationship to our world – social, physical and spiritual.

By our efforts to weave understanding into our buildings, we give them the capacity to carry meaning, to reflect and celebrate life; to help us understand and negotiate change.

Architecture at its responsive and inspirational best can bring gravity and light, body and soul, senses and spirit into play – into dance with both time and eternity, providing spaces in which we can become more inwardly awake, more fully human.

The most inspired art is the result of the artist entering deeply into the form – making process where inner vision and outer means, transform and give meaning to each other.

To see the figure in the block of marble,

To feel the weight of the columns load,

To enter the warp and weave of curving walls

To see ourselves in the unfurling frond

Or the living snake in the mulga branch

– The Spirit finds form –

In this way the artist and the architect have an essential function as integrator and revealer of meaning through images which respond to the deeper impulses of humanity in evolution.

As with an increasing number of indigenous cultures, we are no longer part of a common folk – soul, no longer at one with nature. Notwithstanding the western world’s impressive achievements in science, technology and culture, the price we have paid for the individualising of our consciousness has been spectacularly high – a withering of values that previously connected us to community, land, and the spiritual world, resulting in a world that is sick:- socially, environmentally and spiritually.

We can’t return to the Arcadian oneness but we must find a balance to the prevailing intellectual materialism.

To reintegrate feeling into our intelligence and intelligence into our intuition, so that our thoughts and actions are given a chance to be imbued with sympathy and wisdom, love and joy.

We share with nature processes of metamorphosis – time becomes visible through forms, growth and change – As it does in us as we ripen our humanity.

We stand between spirit and matter becoming conscious mediators in the profound and mysterious reciprocity of materialising spirit and spiritualising matter.

Rilke again –

‘O I who long to grow,

I look outside myself

And the tree inside me grows’

The conception planning and construction of any building can be a richly rewarding complex and challenging process, which sometimes takes years of work with its attendant agony and ecstasy.

Many forces need to be reconciled. The vision with the budget, the building with its context, the design with heritage and building authorities, the co-ordination of consultants, to mention a few – all bring on substantial creative challenges to architect and client alike – and it’s a cause for celebration if they’re all still talking to each other at the end of it!

The Parade College building

This project began with an invitation to submit a concept to the building committee in a limited competition.

I suggested it would be helpful to meet with the College community to gain a more detailed understanding of their needs and aspirations.

The workshops that followed were a real catalyst for the creative process. The intense enthusiasm and open sharing of ideas I found wonderfully stimulating and at times quite moving – one sensed the occasions were graced.

Thomas Carr Centre from the garden

In my experience, when these focused preparatory gatherings have this presence, it augurs well for the seeds that are planted here responding well to nurturing and subsequently unfolding into full expression – the spirit begins to manifest!

Our discussions were free ranging in their attempt to clarify the College’s role for the 21st Century and how its aspirations could be given living expression in the architecture and so act as an inspiration for its unfolding identity in the middle of Melbourne’s urban life. Some of the key suggestions were:

- The building itself could become a celebration of and support to Christian values as they inform education, human development and social justice.

- ‘Faith, hope and love are experienced differently each Century – what is appropriate for now?’ was asked.

- Perhaps the old and the new can dance; masculine and feminine can rebalance; there can be a spirit of inclusiveness, oneness and transparency. There should be order but also movement embracing change.

There were strong statements of faith such as:

- Death and resurrection are one

- The transcendent and the secular can coexist

- Colour and light would be important. It was hoped that both the senses and the spirit could find their place.

- Contemplation, reflection and meditation are all fundamental to theology in this place, which should be a powerhouse for study and faith.

The group felt that the relocation should engage the culture, – not be a churchy billabong.

It should strive to represent the many expressions of Catholic culture – a strong unity in diversity.

Suggested impulses for inspiration were surprisingly varied.

- The spatial awe of the Gothic

- Baroque energy and movement,

- the restraint of Giotto,

- the tension and drama of Rembrandt,

- the tenderness of Fra Angelico,

- the modesty of St Francis,

- the divine Mozart,

- the spirals of Bach,

- the beauty and silence of ARVO Part, the Estonian composer who said

- “this instant and eternity are struggling within us”

The group emphasized that it should be a humane place where community and family are core values, power and humility are wisely balanced, and it should offer a warm welcome to all.

This all taken on board, there followed a short gestation time of challenging intuitive osmosis and much hard work before tabling our design.

It was embraced enthusiastically much to our relief and delight and we were awarded the commission.

First thoughts had been for a strong sweeping connection between Eades Street and Victoria Parade – perhaps a formal Colonnaded garden but this didn’t integrate the old parade College building with the new effectively enough – it was decided it should all become one building connected on both levels.

The design didn’t really change much at all in principle, but certainly developed considerably in detailed design, structure and materials.

To orientate those who aren’t familiar with the building layout –

As you are aware the new building has two public faces which emerge either side of the 19th Century bluestone former Parade College – the main one to busy Victoria Parade with its old trees, trams and traffic and a secondary one to Eades Street to the east – a very pleasant treed avenue.

There is a dynamic and dancing complementarity between the spirit of the old and the spirit of the new – as the new grows out of the old there is both continuity and change. Past and future are both alive in the present.

The old stands tall, sombre and enclosed in its dark bluestone absorbing light while its sandstone trim brings welcome warmth.

The new shows an energised movement, a layered transparency and a lively variety of materials colours and surfaces – playing with contrast and scale.

Both faces of the new building show variations on a free flowing unfolding gesture of connection, of reaching out to the world. This movement also simultaneously embraces and frees the Parade Building to stand in its own traditional dignity yet revitalised in its newfound life and relationship with its offspring.

The new building draws outside space into itself as protected precincts – a sunken garden to Victoria parade and an enclosed courtyard in the centre. The courtyard is being landscaped with a central gravelled area which represents desert, a river of stone runs through it, a seat edges the gravel, separating it from the surrounding garden of pittosporum hedge – veiling the centre and an outer edge of acanthus – giving the contrasting green environment, the feel of an oasis.

A well and fountain, a metaphor for Christ in us forms a turning point for the seat and a focus for the courtyard. This water element will have an inscription from John’s Gospel etched into the steel base.

“But whosoever drinketh of the water

that I shall give him shall never thirst;

but the water that I shall give him

shall be in him a well of water

Springing up into everlasting life”.

This is a quiet space of contemplation, a place to imaginatively engage with the landscape and the building perhaps to meditate on the mystery of baptism- into the church, into Christ.

From this courtyard the sense of the one powerfully animated curve is apparent – one curve but many angles, many views. There are formative life forces at work here, in a state of becoming, a striving for wholeness.

The new movement out of the old is reminiscent of a fan opening, or perhaps the dark blue enfolding of Mary’s cloak both embracing and releasing.

The lines seem to follow a swelling and breathing of the innerspace of the building – the basic pattern is the lemniscape – that archetypal figure described by Goethe in this poem

Nothing is inside,

Nothing is outside

for what’s inside is also outside.

Holy open mystery.

Back to Victoria Parade. Rising up to the right with a surge is the celebratory cross, borne high proclaiming the word to the city.

This is the culmination and point of release for the whole building, its supporting forms spreading open as it meets the earth and it meets the sky, touching in the mediating centre. There is an awareness of shadow and light, an evocation of presence and absence and of power and poise.

Within the form, glazed green bricks, dark and light give a sense of inner growth and renewal.

As we approach the main entrance in Victoria Parade, the footpath widens generously offering a sunny sitting spot looking onto the busy boulevard or into the peace and quiet of the sunken fern garden with its pond.

A gently ramping walkway connects the footpath with the entrance becoming a bridge over the sunken garden. There is a barely perceptible bounce as we negotiate the long span, a quiet prompt that we are suspended – between inside and outside.

We pass under the entrance canopy, a form that simultaneously bears down and rises up like a bow, sharpening our sense of threshold. The glazed doors open, their fine sand blasted geometry divides as we enter regaining its form as they close behind us. We step over the polished orange red marble threshold – warm and radiant – a slice of transformed earth. Its history of place and process are etched into it, reminding us of durability, change and the beauty of the earth.

We’re now in the reception area – an arced glazed space that links all areas of both the old and new buildings around the central courtyard.

Three concrete columns, one larger, two smaller, their surfaces raw, the aggregate exposed, stand stark and grey between the shaded green and water of the centre courtyard to the east and the spill of warm golden light from the stairwell to the west – a subtle resonance with the 3 crosses of Calvary.

An imaginary cross is found too in plan – its long axis connecting the earth and water elements in the courtyard with the light of the stair. Its crossbar coinciding with the 3 columns.

When we take a close look at the stairwell in both plan and section we can see that the geometry underlying it is of a very special kind.

This is the ancient sacred geometry of the vesica pisces or fish’s bladder – a geometry that has remarkable mathematical and proportional properties as well as being rich in traditional symbolism.

The stairwell is the fulcrum of the whole by virtue of its position and luminosity.

In section the larger circle could represent God or Wholeness, division occurs, the two smaller circles setting up a dance of opposites – the overlapping vesica shape is the space of reconciliation, of balance.

If we take the 2 smaller circles as representing the Father and the Holy Spirit the vesica is Christ. Traditionally in Christian iconography we often see Christ (and sometimes Mary) contained in this form. It also has a connection with the fish another of Christ’s symbols.

The intersecting axis of an imaginary cross standing in the centre of this stairwell bisects the vesica at our heart level (where the central light is suspended) so offering the Space proportion of harmonic and symbolic resonance.

As we climb the spiraling stars, which are cantilevered from the wall of the drum, we are simultaneously aware of the resistance of gravity and the uplifting experience of the light above.

A staircase can be a metaphysical event!

This structure is a three dimensional elaboration of the vesica pisces geometry.

The vesica, which would normally complete the 2 circles within the unifying circle of the drum, has been lifted vertically and the perimeter of the vesica and circles have been conjoined by twisting surfaces.

The north circle has a series of spaced battens, penetrated by direct light, while the south circle is a solid surface responding to the changing light throughout the day.

The space between the double circle and the drum is consequently light on the north side, but on the south, it is deeply shadowed

-“and the light shone in the darkness and the darkness comprehended it not”.

Mannix Library

The Mannix library is in a real sense, the heart of the new college with its magnificent collection of manuscripts and books and excellent study facilities. The books fill a large internal space protected from direct sunlight.

A musically rhythmic undulating ceiling moves over them, gathering the space as it rolls westward rising into the light filled mezzanine volume. This is to maintain a quiet connection between knowledge and wisdom.

The view down between the rows of shelving rests on the green foliage of the Eades Street trees.

Around the edge of the book storage is the circulation area – a low space, its windows fanning like the pages of a book as they shift and frame many vignettes of the old building, the courtyard and the street trees.

On the edge of the curving edge between the circulation and book storage are a series of ceiling openings modulating daylight to study carrels below.

From the outside we see the roof both rising and cascading eastwards in response to the ceiling and the eye- like window that light the study areas.

And we can appreciate from here the directed energy of the overall movement of the building – a movement of gentle receptiveness and energetic giving.

From the mezzanine an impressive overview opens up – sweeping from the crosses on the apex of the old chapel to the Dandenongs on the eastern horizon, and inside, an overview of the library itself.

An extensive skylight runs the length of the mezzanine directing light down into the library workroom as well as into the mezzanine itself.

Light has been worked with consciously as an important physical and psychological element in the building – its quality being critical in creating an appropriate ambiance and a feeling of well being.

It is also symbolically powerful in its association with the Spirit, with conversion and with illumination.

Goethe talked about colour being the deeds and sufferings of light. Colour and contrast are important to bring life and harmony to space.

The silent struggle between light and dark is everywhere in architecture – it can be dramatized as in the stairwell, bring a mood of steady warmth and dignity as in the boardroom, be a support for quiet thinking and concentration as in the library, or a surrounding earthy radiance as in the staff and student lounges.

The violet brings together in balance the colour and warmth of the earthly life and the blue of the spirit, the mind, the abstract. The dark cobalt blue, tiles and bricks I feel connects us with depth – of thought of tradition – of water and flow. The light plays with the viscosity of the glaze.

I have the firm belief that even in our overwhelmingly secular country and in these times of rapid cultural transition and uncertainty that…

Architecture can embody the Spirit,

can be infused with,

enlivened by,

and be vibrant with it.

That it can be an evolving reflection of us and the great mystery beyond ourselves –

can bring insight to the meaning of the relationship between fragmentation and wholeness

it can reflect and hold ideas, ideals and aspirations,

be a vehicle for understanding and nurture the inner life

it can be a source of inspiration joy and challenge, a humanising refuge, a place of healing, a catalyst for love and a recipient of grace.

I believe that when we enter the mystery of the creative process, the forms we make embody ourselves and our understanding (and sometimes more than our understanding) and bring into a dynamic and living conversation what we were, what we are and what we could be – the challenge of transformation.